15 Staples That Appeared On Medieval European Tables

Pull up a wooden bench and imagine the clatter of trenchers, knives, and goblets in a candlelit hall. Medieval European tables held familiar flavors alongside surprising ingredients you might not expect.

From rye loaves and pottage to almond milk and spice-scented wines, each dish tells a story about class, climate, and clever resourcefulness. Ready to explore the tastes that fed peasants and nobles alike?

1. Rye Bread

Rye bread anchored daily life because rye tolerated cold, damp fields where wheat struggled. Loaves were dense, sour, and satisfying, baked in communal ovens or hearths.

You would tear off hunks to scoop stews, or pair slices with cheese and pickled fish.

For poorer households, rye meant survival during lean harvests. Wealthier tables still served it alongside finer wheat, valuing its heartiness.

Spices or honey sometimes appeared in festive loaves, though salt was precious.

Crumbs caught sauces, crusts softened in broth, and stale pieces became pudding. Simple, sturdy, and sustaining, rye bread kept bellies filled through long winters.

2. Pottage

Pottage was the everyday stew, endlessly adaptable to seasons and status. Imagine a cauldron simmering over the hearth, bubbling with barley, leeks, herbs, and whatever garden greens you had.

Meat scraps, if available, turned it richer, while peas or beans gave protein.

You ate it with bread or straight from wooden bowls. Thick or thin, it warmed bodies and stretched ingredients wisely.

Cooks layered flavors with onions, parsley, and a pinch of precious salt.

The beauty was practicality; nothing wasted, everything reused. Yesterday’s leftovers enriched tomorrow’s pot.

Pottage defined medieval comfort food, nourishing households from sunrise to dusk.

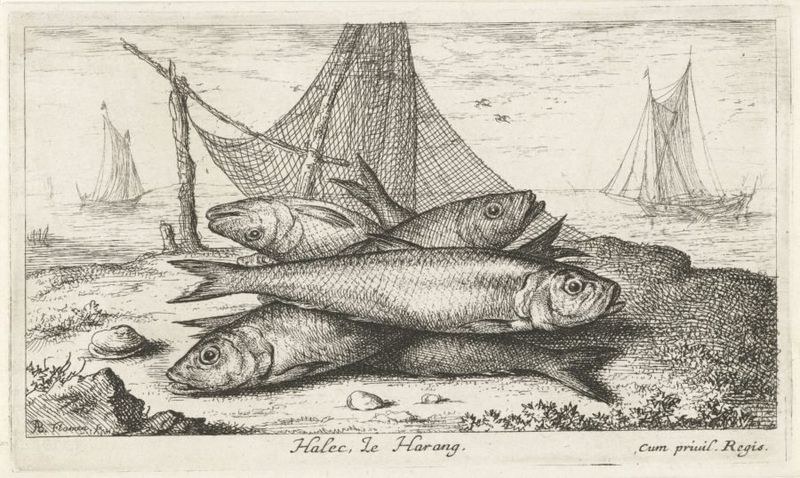

3. Salted Herring

Salted herring traveled far inland, carried by merchants and fasting seasons. Salting preserved the fish for months, making it a dependable protein when fresh catch was impossible.

You would soak and cook it, then serve with mustard, onions, or rye.

Church calendars encouraged fish on many days, so herring fit the rhythm of the year. Coastal fisheries boomed, fueling markets and guilds.

Barrels stacked in storerooms meant security when fields failed.

The flavor was assertive, briny, and beloved. Paired with ale or thin wine, it satisfied.

Herring tasted like the North Sea and bustling medieval trade.

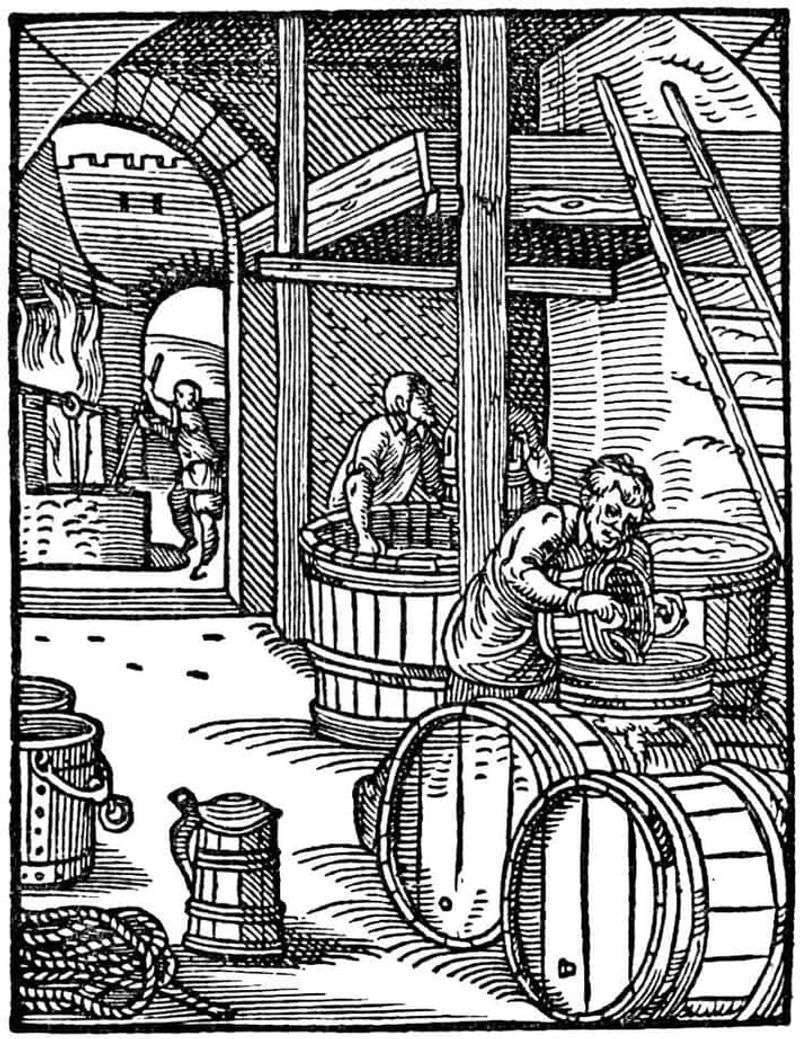

4. Ale

Ale was safer than much water, brewed in homes and monasteries alike. Think cloudy, low-alcohol drink served fresh, sometimes flavored with herbs before hops spread widely.

You would sip it daily, not just for celebration, and children drank weak versions.

Grains like barley or oats formed the mash, with yeast doing its quiet magic. Alewives ran neighborhood breweries, their reputation vital.

Kegs rolled to feasts, wages, and fairs.

The drink paired with bread, fish, and stews, smoothing rough edges of salt and smoke. In cold months, warm ale comforted.

It was nutrition, hydration, and community in a mug.

5. Cheese

Cheese solved the problem of surplus milk, storing nourishment for lean seasons. You might taste fresh, soft curds in summer, then hard wheels in winter.

Monasteries perfected techniques, pressing, salting, and aging in cool cellars.

From goat, sheep, or cow, cheese crossed social lines elegantly. Peasants shaved it over pottage, nobles paired it with fruit and spice.

Rinds protected precious interiors during travel and trade.

Salt, time, and patience transformed simple curds into complex flavors. A small slice went far, especially with coarse bread.

Cheese was dependable comfort, a tangy signature of each village.

6. Peas and Beans

Field peas and fava beans powered bodies with plant protein. You would find them dried in sacks, ready to boil into hearty stews or mash with herbs.

On fast days, they replaced meat, filling bowls economically.

These legumes fixed nitrogen, helping soil recover for future crops. Kitchen gardens spilled with pods in summer, then drying strings hung near the hearth.

People seasoned them with onions, garlic, and a splash of vinegar.

Simple, earthy, and satisfying, peas and beans anchored pottage and pastes. Add barley, and dinner was complete.

Their reliability made them beloved across medieval Europe.

7. Cabbage and Brassicas

Cabbage, kale, and turnip greens thrived in cool climates and rough soils. You would chop them into pottage, braise them with fat, or ferment them to last winter.

Their sturdy leaves arrived when orchards slept.

Gardeners prized hardy varieties that endured frost. A kettle of greens with onions and lard made a comforting side.

On lean days, cabbage still felt substantial with vinegar and herbs.

Monastic gardens cataloged cultivars, sharing seeds and wisdom. Greens brought necessary vitamins to heavy bread diets.

Humble but vital, brassicas colored medieval tables with reliable, resilient nourishment.

8. Pork and Lard

Pigs turned scraps into meat, making pork the commoner’s dependable animal. You would see bacon slabs, sausages, and salted cuts hanging from rafters.

Lard flavored pottages and pastries, stretching scarce butter further.

Autumn slaughters filled tubs with rendered fat, cracklings, and salted joints. Smokehouses worked tirelessly as nights grew long.

Even small households kept a pig for winter security.

Herbs, garlic, and pepper, if affordable, seasoned the meat. On feast days, roasts crackled beside apples and onions.

Pork’s versatility and lard’s utility kept kitchens running efficiently through hungry months.

9. Trencher Bread

Trenchers were thick slabs of stale bread used as edible plates. You would ladle sauces and meats on top, letting juices soak in deliciously.

After the meal, trenchers fed servants, the poor, or pigs.

This practice saved dishes and absorbed flavors, a practical solution before widespread pottery. Wheat trenchers appeared at wealthier tables, while rye versions handled daily fare.

Knives did the cutting, fingers did the rest.

At feasts, spiced gravies transformed humble slices into treats. The habit taught thrift and generosity simultaneously.

Trenchers turned bread into tableware, then back into nourishment again.

10. Almond Milk

Almond milk was the elegant, dairy-free solution for fast days and delicate stomachs. You would grind almonds, steep them in warm water, and strain to create a creamy base.

Cooks used it for sauces, soups, and desserts.

In noble kitchens, almonds were a prized import, so this milk signaled wealth. Spices like cinnamon or ginger often joined the pot.

Recipes appear frequently in late medieval cookbooks.

It carried sweetness, body, and subtle flavor when cow’s milk was forbidden. With sugar or honey, it felt luxurious.

Almond milk turned simple dishes into courtly fare without breaking religious rules.

11. Spiced Wine (Hippocras)

Hippocras turned rough wine into a fragrant treat using sugar or honey and warming spices. You would sip it at feasts, cheeks flushed, savoring cinnamon, ginger, grains of paradise, and cloves.

Strained through a cloth, it gleamed ruby and clear.

Spices cost dearly, so hippocras announced status and generosity. It often appeared at the end of meals, aiding digestion and conversation.

Recipes varied by region and host.

The drink traveled with physicians’ advice and merchants’ bags. Even small pours felt memorable.

Hippocras stitched trade routes, gardens, and kitchens together in sparkling, aromatic harmony.

12. Onions and Leeks

Onions and leeks were constant companions, building flavor from the pot up. You would slice them into pottage, pies, and fish dishes, softening their bite with slow heat.

Their storage life meant reliability through winter.

Garden rows yielded bulbing onions and slender leeks side by side. Medicinal lore praised them for vigor and warmth.

A cook’s knife rarely rested without their whispering sizzle.

They paired with bacon, herbs, and vinegar gracefully. In Lent, they lifted simple legumes.

Humble yet essential, onions and leeks made ordinary ingredients taste like home.

13. Barley

Barley was the workhorse grain, cheaper and hardier than wheat. You would find it in bread blends, pottage, and ale mash, lending nutty heft.

Peasants depended on it when harvests wavered.

Pearled or whole, it thickened soups and stretched scarce meat. Fields of barley rippled across cooler regions, feeding humans and animals alike.

Monks recorded yields meticulously, managing granaries with care.

A bowl of barley and greens satisfied after hard labor. With herbs and onions, it turned comforting quickly.

Barley’s modest flavor supported the table quietly, day after hardworking day.

14. Apples and Pears

Orchards gave apples and pears for fresh eating, ciders, and tarts. You would stew them with honey and spice, or dry slices for winter stores.

Even simple apples brightened salted meats and heavy breads.

Grafting techniques spread varieties across abbey lands and manors. Cellars cradled baskets in cool air, preventing bruises.

On feast days, fruit pastes and pies delighted guests.

Cider refreshed laborers, while perry accompanied autumn slaughtering. The fragrance of baked fruit felt like home.

Apples and pears balanced the medieval table with sweet, tart comfort through the seasons.

15. Mustard

Mustard cut through richness when meat was fatty or fish very salty. You would grind seeds with vinegar or verjuice, creating a sharp, lively sauce.

It accompanied sausages, herring, and roast pork beautifully.

Humble seeds hid impressive power, storing well and costing little. Monasteries cultivated plots, and markets sold portable mustard balls.

Cooks adjusted heat by sieving or mixing brown and yellow seeds.

That tang woke up tired palates and enlivened leftovers. On fasting days, mustard made legumes sing.

Small spoonfuls brought balance, proving condiments mattered as much as main dishes.